Stacy Bloom Rexrode

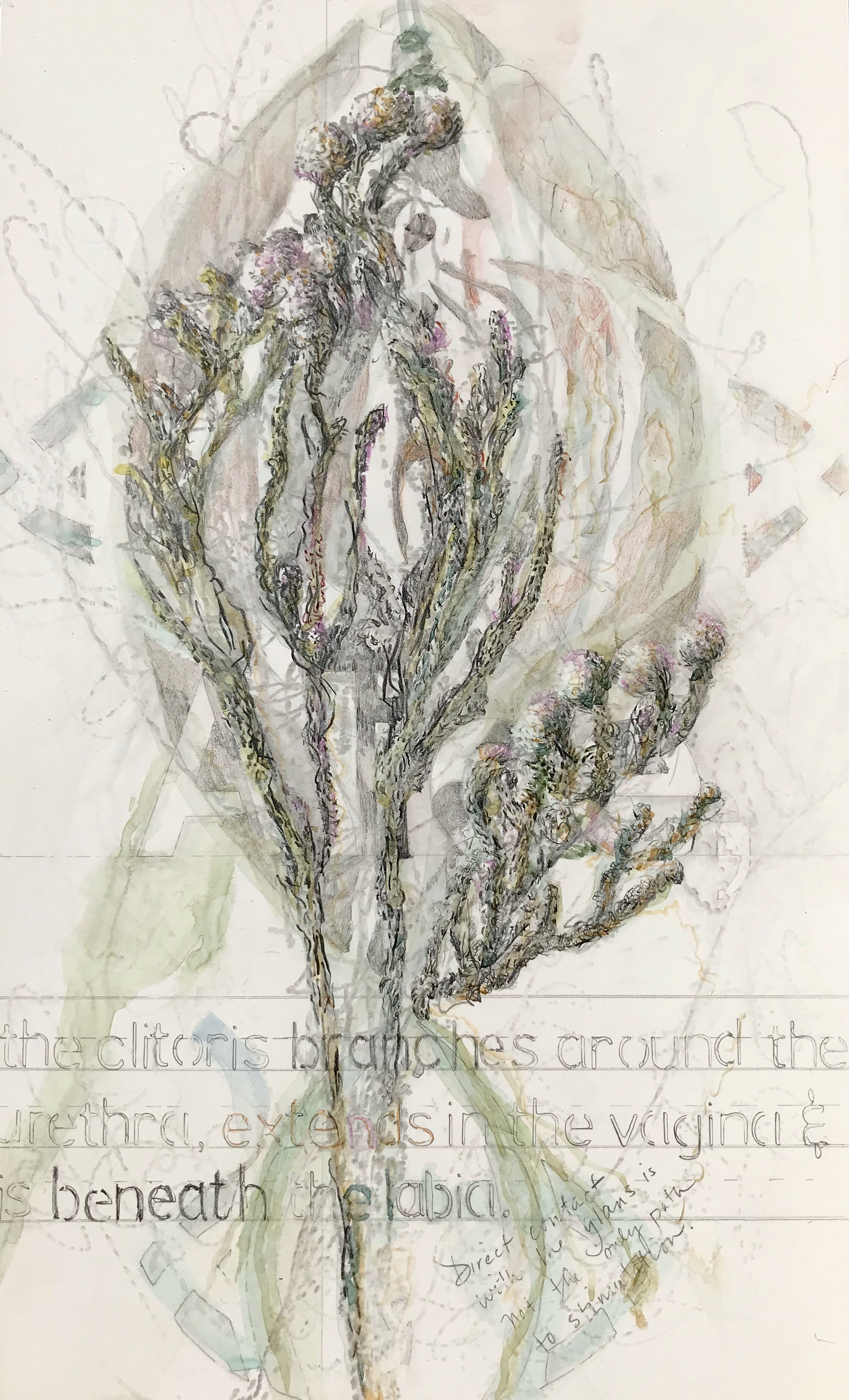

Flora Fem Fauna (Installation View)

Stacy Bloom Rexrode

“The flower throughout art history has been tied to feminism, feminine, fertility, all those things. I think we, all of us in this show, wanted to take that back and say, ‘We can be feminist and we can be feminine.’”

– Stacy Bloom Rexrode

The four-artist show Flora Fem Fauna at Meredith College had been on my list for weeks to visit. So when I received Stacy Bloom Rexrode’s email inviting me to walk through with her, I jumped at the chance. It is always more fun to experience an exhibition with the artist. Within about 10 minutes of chatting, I was like… “Stacy, I have got to record this.” I just loved her take on feminism, her thoughtfulness with her art and the times. There was a give-and-take within our impromptu interview, and we often finished each other’s sentences as if we were old friends. We rambled and we philosophized.

I love it when life shows up in unexpected lovely ways and hope you enjoy reading this informal interview as much as I loved having it.

We enter as Stacy tells me how the show began… when I pulled out my phone and hit “Record.”

Elizabeth Mathis Cheatham: Tell me about this piece. I actually will tell you when I first looked at the pictures of the exhibition, it was my favorite, even before you’d reached out. I’m super interested in how you started, how you added onto it.

Stacy Bloom Rexrode: Sure. I guess I will go back to the very beginning: inspiration. Certainly my research into feminism and the idea of third- and fourth-wave feminism where nature is considered a topic—there’s a lot of parallels between nature and women and underrepresented people and how we don’t honor nature. And so there were all these parallels I was seeing. I was lucky enough to go to Venice in 2013 and went to a Murano Glass Studio and just loved the idea of craftsmanship and how that trade is passed down from generation to generation and my theme is always taking—

EMC: Is this a Starbucks cup?

SBR: Yes.

EMC:Wow. Sorry, keep going. All these treasures!

SBR: So my personal thing is how we as a society assess value, and so often how we name things translates into the perceived material worth of things. I wanted to take that same idea of craftsmanship from the glass studio and use a material that is literally trash, and so I started collecting all of my household recyclables, which my husband is really not happy about. Kind of a hoarder now in our garage. These are all—initially I just tried to do my household and those were a couple of the early, smaller works, but now I collect from when I go to an occasion—like these were from a gathering my brother had. I saw the brown Solo cups and I thought, ‘Oh, those are fabulous.’ Especially colored plastic, I try to save that and use…This is a paint tray. That’s also a paint tray that I was painting the interior of our house with. Medicine bottles. Perrier bottles. This is my daughter’s. She was very happy that I included her Wendy’s Frosty cup. It all ties into—I’m a big art history buff, and I was studying Dutch masters 1600s to1800s. The idea of how painting flowers up until that time had been called a “women’s pastime.” Then men take it over, and all of a sudden…

EMC: It’s elevated.

SBR: Exactly. Completely in the canon. So I dug into that a little bit deeper and realized that it was tied into what was going on at the time. It was the onset of the bulb production and horticulture. These bulbs were so prized and so expensive that most people couldn’t afford it, but they could actually afford the paintings, so people would have these paintings in their homes. They portray these flowers together that of course would never bloom at the same time. It’s like a vanitas kind of compositions, so to speak.

Perpetual Patterns (Detail)

Stacy Bloom Rexrode

Still Life with Flowers with Imposed Presence (Detail)

Stacy Bloom Rexrode

EMC: So I'm learning to ask questions when I don’t understand. I'm not familiar with the word “vanitas.” What does that mean?

SBR: It's a type of still life, but really when you choose objects that have these hidden meanings. So now this one—this is a giclée of a 17th century still life, so they can reference the idea of life passing in the wilting flowers. Some of them have skulls or chains and that would represent mortality. If you put shells or things like that, that would show a material worth and reference travel and worldliness… so it would have these hidden meanings within the still life.

EMC: Thank you.

SBR: So I wanted to build on that idea that we’re such a consumerist society, if we continue not to value our resources and have this accumulation, we’re going to end up with this in your home. We’re not going to have our natural resources and access to them just as they couldn’t afford the real bulbs. So it’s my play on that sense of value.

EMC: You have acknowledged that while this piece is so beautiful… in actuality, it is not what you want to be left with. You want the nature, you don’t want just the—

SBR: Exactly. And that's the sense of irony. I’m not trying to pound it into somebody’s head. I want them to have that conflict. In fact, I’ve been dismissed because of them being beautiful, and it's not maybe what’s current in the arts sometimes today. So I get dismissed for them being too pretty, which is common throughout most of my art, so I do deal with that.

EMC: That’s frustrating. I think that that, too, shows what we put value on and who the people are who are—

SBR: Making those rules.

EMC: Making those rules.

SBR: Yes. I agree.

EMC: When I first saw information on the exhibit, I immediately thought of the cyclical characteristics of nature and women. I often wonder when feminism is saying, ‘We can do everything anyone can do,’ and when it is say instead, ‘Listen, we aren’t always linear and there is power in that.’ We want to do things differently… I think it really depends on the person and what rings true to them.

SBR: Absolutely. Yeah. Totally…The flower throughout art history has been tied to feminism, feminine, fertility, all those things. I think we, all of us in this show, wanted to take that back and say, ‘We can be feminist and we can be feminine.’ They don’t have to be separate; they can be illustrated so that femininity can also be a strength.

EMC: Yes.

SBR: I think that ties into what you were saying.

EMC: Absolutely. That can look so different for people; it doesn’t have to be this box that we’re put in or that we feel like we need to stay in.

SBR: Exactly. When I went for my Master’s, I remember I had professors when I knew that I wanted to focus on the idea of feminist arts who said, “You’re going to pigeonhole yourself and why would you do this?” I’m kind of jumping all over the place here, but I remember studying art history and learning about German expressionism and that activism and how artists were trying to change politics and that was the aha moment for me of, ‘Wow! Art is not just simply something to look at and take in but can have power.’ So taking that, and then starting to learn about Womanhouse and Judy Chicago and all those groundbreakers. Lynda Benglis. And that was the power I wanted.

Foreground: Perpetual Patterns (Detail)

Background: Still Life with Flowers with Imposed Presence

Stacy Bloom Rexrode

“By pulling together under that feminist umbrella, we can rise and raise everybody up.”

– Stacy bloom Rexrode

EMC: Yes… Judy Chicago is one of my favorites. Okay, this fabulous mannequin…?

SBR: I will tell you that I completely underestimated the amount of time that was going to take to do all this needlework.

EMC: I’m sure. I want to try to figure out how I can get close without touching.

SBR: Oh you can—Absolutely, yeah. I, for the last two and a half weeks, would leave work, go home, and work until 2-3 in the morning and all day Saturdays and Sundays so my fingers were raw. I was sitting there two days before the weekend we were going to install, and I was like, ‘I hate art! Why I am I doing this to myself?’ When we brought everything in and dumped it, they just went crazy over it and said, ‘Oh my God!’ And immediately I was like, ‘Never mind. I love art again.’ But having that camaraderie and that support from—it’s so solitary sometimes being an artist, and so to have that group just be there for one another throughout this whole process, that was my big takeaway from this. I’m trying to hold onto that, like even if we don’t show together, maybe studio visits and coffee. Sometimes we need that little bit of, ‘You’re doing okay! It’s hard but—’ So that’s my little side note on her.

In my art history obsession, I found this etching by—I’m trying to think of what his name is now… Jacques Le Moyne, I think. It was an etching of a Pictish warrior woman, but the body on the etching had these flowers all over it. So I dug back farther, trying to learn about Pictish women.

EMC: Yes. I don’t know anything about Pictish women.

SBR: I had never heard of it, so I started researching it, and it turns out it was a tribe before Scotland was Scotland. The northern region, they were located there. It really was egalitarian, very equal society where the women fought next to the men. They were notoriously vicious because they would show up for battle completely nude with— they’re not sure if they were tattooed or painted, but they would paint or decorate their bodies. And it’s northern Scotland, so it’s cold. They would intimidate their opponents often just by showing up nude to fight, and the women were right there next to the men. I was really just intrigued by that idea and thinking about how I deal with nature and the idea of Mother Nature is often passive and—really just letting my thoughts go everywhere, thinking about how we need to be warriors for the environment and climate. I wanted to do my take on that and kind of took Jacques Le Moyne’s idea of the flowers. I actually am hoping to take the body suit and do a video piece at some point. I have two daughters, so one of them is—they don’t know it yet—but they…

EMC: They’re going to be the model.

SBR: Exactly. So I’m hoping to turn this into a video piece.

EMC: Has sewing always been something you’ve done or—

SBR: This is my first actual attempt at embroidery, so why not go big?

EMC: So help me to understand. When you say embroidery vs sewing, how do you define those differently?

SBR: Really, just the decorative aspect of it. The idea of women’s handicraft has really been important in my work. I crocheted that gray piece back there as well. My grandmother would probably never refer to herself as a feminist in her lifetime, but she was the strongest woman I knew. They had a working farm, like 200 milking cows. She would work all day in the barn and cook for everybody and the crew. Then, at nighttime, she would come in and she was always working on either a blanket or she would crochet the little doilies and things. So I grew up watching this women’s handicraft. For me, I use those elements as a sign of strength in women and the idea of passing down—she taught me how to crochet and how to do these things.

EMC: As you said this, I had this recollection from Gone with the Wind where Scarlet’s mother was always mending as if a woman was never supposed to be sitting without work in their hands.

SBR: Yeah!

EMC: Do you feel like for your grandmother when she was finished working on the farm—and it can be both—but that the sewing and embroidery and whatnot was meditative and her art, or do you feel like that was just more work she was putting on herself?

SBR: I honestly think it was more of the first, the meditative. I think with the labor-intensive work in the barn and that kind of thing, I think it was her way to finally allow herself to sit. She was a riot. She loved football and she loved wrestling. Which, she was—I don’t know if you know much about religion, but she was Church of the Brethren, so it’s like Amish/Mennonite Church of the Brethren. So she wore the doily and always a dress; she worked in a barn in a dress. To see this—I’m 6’1” and she’s about 5’2” maybe, so to see this tiny woman so strong! One of the kindest, most giving people I ever knew in my lifetime. It was really that connection of strength with the idea of her sitting there ritually, and God knows she made a ton of them! So everybody had blankets; everybody had doilies.

EMC: You mentioned that you think she never would have called herself a feminist. I think that “feminist” has taken on so many different meanings. It was kind of a curse—it was an insult. Earlier you said you considered yourself a feminist artist. How do you define that for yourself?

SBR: I do. I think you hit it. I’m always surprised when I come across really strong women who can’t identify as that. I think it’s because those early waves were so rebellious and in some ways, not welcoming, like it was my-way-or-the-highway kind of thing. I clearly identify as a feminist, because, at our talk Holly really hit on it in saying, we want everyone. It’s about equality for everyone. It’s not just female pursuits. It’s anybody that believes that everybody should be treated equally. So we’re not trying to say, ‘Put us above everybody else.’ It’s really just promoting equality across the board, especially for those communities that are forgotten and discounted. By pulling together under that feminist umbrella, we can rise and raise everybody up.…

Above are pieces from two of the three other talented artists that made up Flora Fem Fauna.

Jenny Eggleson (Paintings)

Holly Fischer (Sculptures)

Above is a piece from one of the three other talented artists that made up Flora Fem Fauna.