Stacy Lynn Waddell

Photo: Olly Yung. © 2020 Matrons & Mistresses.

“The power that I have as an artist is that I can create and I can create imagery that extends that story, that revises that story, and that shapes it in a way that is inclusive of me, my ideas and my ideals.”

– Stacy Lynn Waddell

Stacy Lynn Waddell was supposed to be one of Matrons & Mistresses’ first interviews. However, when a gas line exploded a few blocks from her studio the day before our photo shoot, we decided to wait. What follows is the interview that we completed a few weeks past—almost a year after we had initially scheduled. Once again Time had another plan… And, as usual, She was right.

I have read Stacy’s interview over and over again this last week to see if I could shorten it a bit to protect y’all’s time. But I could not seem to remove a word. So, instead, we have decided to share Stacy’s interview in stages and to let it mold some of our future articles. Stacy is brilliant and each time we speak, I am blown away by how beautifully she conveys her art into words.

Photo: Olly Yung. © 2020 Matrons & Mistresses.

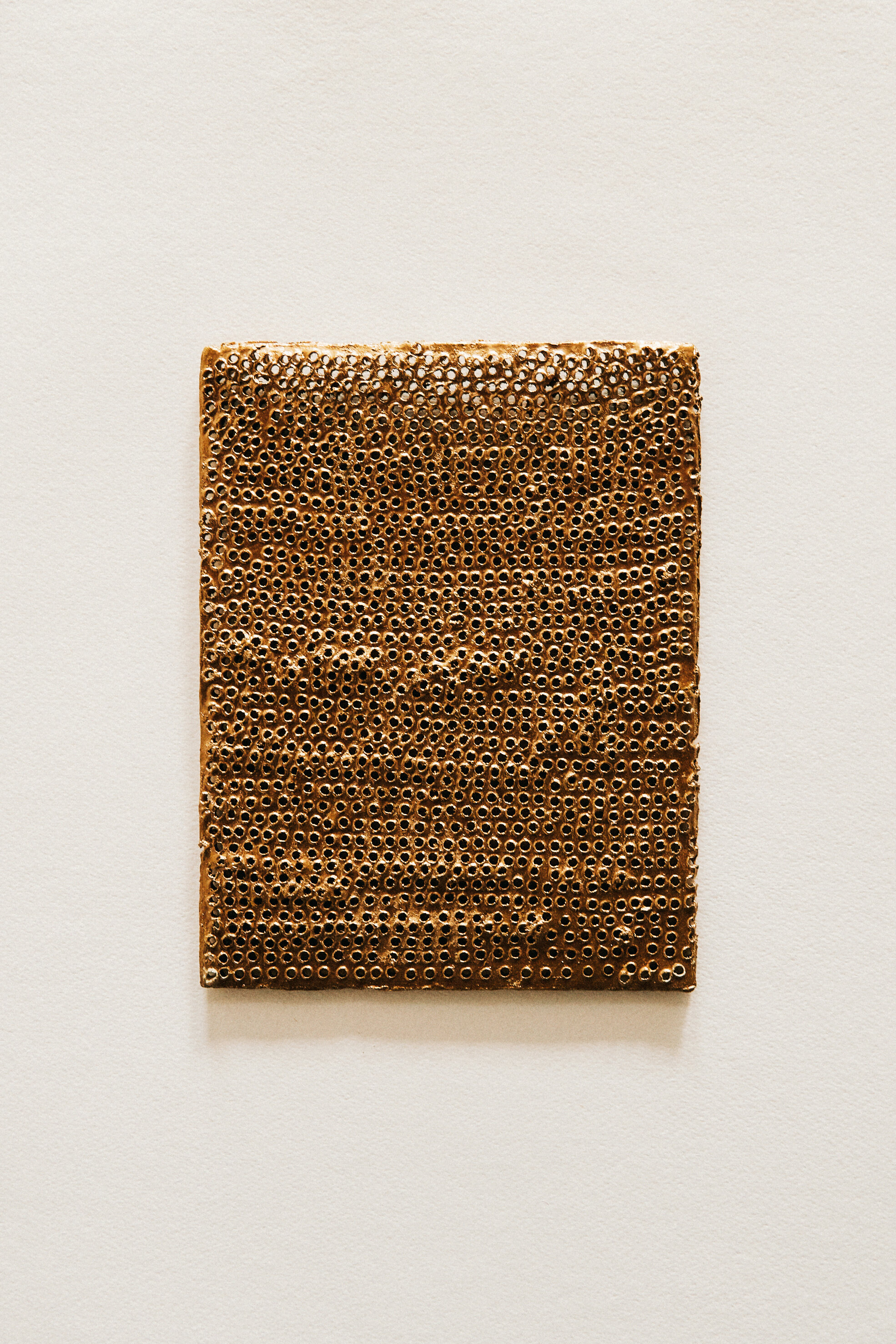

In Background:

Goldenhot Butterfly Queen, 2015

Stacy Lynn Waddell

Elizabeth Mathis Cheatham: Thank you for doing this! I am so excited to chat. I would love to just start by you telling us a bit about yourself and your art.

Stacy Lynn Waddell: About myself and my art? Wow. I think maybe the most important thing to mention is that I had a very supportive mother early on who paid very close attention to what we were interested in. I’ve always loved reading, making things and other activities where I can work solo, for whatever reason. I was a very independent kid. She recognized that and immediately put things in front of me that I could respond to, so I think in large part I’m an artist today because of that. We lived artfully. It’s not as though there was lots of art on the walls or that I actually knew artists because I didn’t, but just the way she approached our daily life—there were always bits of inspiration involved in that. She could take very mundane activities and make them really fun. Learning how to think, learning how to move through space, and turning all opportunities into a learning opportunity was something that has been really pivotal for me.

EMC: That was a broad question!

SLW: I know! ‘Tell us about your art!’ My work investigates beauty and transforming the surface, whether it be paper or canvas, to attract the eye. Precious metal leaf allows me to employ the sheer optical power of shine, sheen and reflection. Gilding started as an additive to a mostly monochromatic, plus maybe one color, overall scheme, and then leaf became a material unto itself around 2010 or ’11 or ’12. I started to think about how to harness something that has an embedded cultural value, like in vernacular references to bling or gold, in terms of the world’s economy and all of those things that we think about relating to gold being an ancient substance that is still being mined. I wanted to really harness the power of a material that shifts between the ancient and the contemporary.

Also, I’ve always been really interested in materials and processes that say so much more about the work than I ever could write about it or talk about it. So if you burn paper or paint a reactive substance on a surface and activate it so that it comes into being like a photograph, all of those things embed the work with a type of mystery that I want people to get caught in. The net of surface attraction that you could get caught in, or this net you could get tangled in thinking about the process—looking at something and not fully understanding how it’s made and asking the question, ‘What’s that?’ ‘Oh, I’ve never seen that before!’ My tools and materials aren’t really standard fare. They’re craft-based tools; they’re blacksmithing tools; industrial tools; kitchen-sink alchemical processes; It’s a mishmash of approaches and hands-on experiences I want to have on a journey to creating a more personal visual language.

So I think on the one hand, the work is about transformation and alchemy and kind of—not trickery, but a magic. A process of creating something that appears in which people are stumped by, perhaps even skeptical of, and then curiously attracted to. The other part of the process of my work is rooted in an effort to revise imagery. I’ve made a lot of works after classic paintings—classic American and European paintings, where I’m starting from that place of history and classism. I’m thinking about what it means to look at a work and not necessarily see yourself reflected, or see things about yourself reflected that are one-dimensional, that don’t necessarily tell the full story. The power that I have as an artist is that I can create and I can create imagery that extends that story, that revises that story, and that shapes it in a way that is inclusive of me, my ideas and my ideals. So those are the two strands, I think, and if you add them together, that’s what the work is. It’s a kind of revisioning or reclamation project, where I try to lull you and I attract you with things. Then hopefully you will invest the time to stand in front of one of my gilded canvases or works on paper, and negotiate the reflected shine and sheen by moving your body around the piece. That’s the only way to take it all in, right?

EMC: Absolutely, because it looks so different dependent on the angle and time of day…

SLW: You have to have a physical relationship to these works. You have to engage. And it’s a slow observational process.

EMC: I think I’ve heard you call it a "slow glance”?

Photo: Olly Yung. © 2020 Matrons & Mistresses.

On Left:

Untitled (skin/lace), 2019

Stacy Lynn Waddell

On Right:

Untitled (self portrait as a bust with werewolf wig as seen as a reflection in a mirror), 2019

Stacy Lynn Waddell

SLW: Yes. Very slow. It’s very much about slow. All of the gilded work is situated on top of an article that I read in the New York Times in 2015. Jennifer Eberhardt—a social psychologist at Stanford University—does extensive research on racial profiling. The whole crux of racial profiling is not taking the time to genuinely see and know. The way it works is that at quick glance—I didn’t say look or observe—at a very quick glance, danger or threat is seen to appear in something that is darker or darkly or that has particular attributes that are very quickly read, but never ever considered beyond the surface, beyond a kind of attachment to a kind of chart of—okay, if you see this shape, or this tone, or this color, there’s danger. I found an interesting correlation between this faulty way of looking and those of us that are trained lookers in the art world. How many times have you been to a night of openings, or attended Armory or Frieze and it’s packed with people so you stand and just sort of crane your neck in order to say that you actually saw something? Of course—this was back when we could be around people.

EMC: In the old days!

SLW: You just crane your neck and you do a quick glance and you think that you’ve seen something, and you really have not. You haven’t seen it; you haven’t engaged with it; you haven’t created a relationship. I’m all about the observational process being the relationship that you’re having with this thing that you’re taking in through the eye. I think that my work asks that of people. It’s one of the reasons why photography—even really, really good photography— falls short as a means to document my work. I’m usually unhappy with the work photographed and my photographer is one of the best!

EMC: Because you have to experience it!

SLW: You do.

EMC: It is so dimensional and alive! This might seem really weird, but with my piece that I have, it’s like it almost has moods. I engage with it very differently depending on the day. It shows up one way and I another. It’s this real conversation that you can’t get with just looking at a flat image of the piece.

SLW: It’s true. It’s very, very true. It’s interesting. For me, I’m always thinking on a formal level about how people are going to look at the work, how they’re going to take it in. I’m in the studio and I’m always looking at a piece, going like, ‘Wow! I wish there was a way to have people only engage with the work in person.’ How does that happen? What I’ve been doing recently for people that are interested in seeing a particular piece, instead of sending them a still image…

EMC: You’re sending a video?

SLW: I’ll do like a little video. Like a little sixty-second-or-less video where I’m in front of the work, and then I kind of move around the work, going in close to show details. I just find that that seems to render the pieces better when I want to share them…I don’t know if I really answered your question.

EMC: No, you answered it beautifully! And you kind of hit two points there. This idea of a slow glance and how you want people to interact, and this also retelling of history in a much more accurate way. Am I kind of—?

SLW: Well, accurate—yes, accurate but—I think the term “accuracy” for me attaches itself to a statistical data, like ‘Ok, we want to make sure that the numbers are right. We want to make sure that the dates are right.’ We’re having a conversation about it and that you said “accurate” really makes me think… It’s to show the full range of humanity of our shared experiences, and the only way to do that is to have that reflect everyone. We’re having this conversation globally now because we watched a man, one of many, be murdered in front of us. I think that, of course coupled with people coming out of quarantine and having so much angst about COVID-19 and the loss of income and so many questions about the future, was like gasoline on a fire. But it’s so evident the way that we need to look at the world around us or our neighbor or our town or our city. It’s just about reflecting a shared humanity. When people aren’t included in that story, it says that you’re less than human, that you’re being denied the ability to be considered in the most fundamental regard. We can’t address and deliver on the full range of human and civil rights inequities because we’re not even at a baseline! I think my work is trying to say that we need to get to this place, so that we can get to the next place. Here’s the horizon line where we all should at least be standing on. We all should be ships going along that line.

Photo: Olly Yung. © 2020 Matrons & Mistresses.

Hot Head, 2007

Stacy Lynn Waddell

Photo: Olly Yung. © 2020 Matrons & Mistresses.

Untitled (distressed and gilded paper study), 2016

Stacy Lynn Waddell

“It’s just about reflecting a shared humanity. When people aren’t included in that story, it says that you’re less than human, that you’re being denied the ability to be considered in the most fundamental regard.”

– Stacy Lynn Waddell

EMC: Yes, that is such an important and powerful point—thank you. As I was preparing for our interview, I was revisiting your CV. In addition to some great shows, you’ve had some pretty impressive residencies. The Joan Mitchell Center in New Orleans is one of them. Recently, you were splitting your time between New York and North Carolina due to being in-residence at QueenSpace. Will you speak a little bit about your experience between the cities, and how you’ve decided to be an artist living and creating in Durham?

SLW: For a long time I didn’t go anywhere. I finished grad school in 2007 and I went to Houston and did a residency in 2009. I did something at Elsewhere in Greensboro in 2011, I think—I’ll have to look at my CV again, I can’t remember. Then I just didn’t go anywhere really. I was applying to certain residencies that I really wanted to focus on, but I wasn’t getting in. I applied and I applied and I applied. Then all of a sudden, they started to happen. I started to get yes’s. Which is great.

EMC: Yes’s feel good, don’t they?

SLW: Feel really good. Looking back on all of the no’s, the yes’s came at the exact right time. A residency is great and being able to go and live in another city and another place amongst a new cohort of artists can be really, really productive. The timing was perfect, my particular engagement with my materials, all of it sort of came at a time when it made sense. New Orleans and the Joan Mitchell Center happened in 2017 and that was really fantastic, especially because of the timing. When you get accepted to that residency, they give you a first, second, and third choice of when you’d like to come. I knew that Trevor Schoonmaker’s iteration of the Prospect Biennial, was going to be opening the fall of 2017 and I thought, ‘Wow. It would be really amazing to be in New Orleans and do a three-month residency during that time.’ So that was my first choice and I thought, ‘I’m probably not going to get that, because everybody that’s aware is going to…

EMC: Going to have that thought.

Photo: Olly Yung. © 2020 Matrons & Mistresses.

Sparkle, 2006

Stacy Lynn Waddell

SLW: But I did get it, the three-month slot for that time. I thought, ‘This is going to be great.’ Well, what I did and didn’t quite anticipate was just the sheer amount of—the way in which the city of New Orleans was going to overwhelm me in the best possible way. The Second Lines, the food, the culture is so dense and rich and amazing that you could likely go somewhere for three months and you’re supposed to be making art, but you’re really getting to know the city. And boy, it was amazing. It was fantastic. I did manage to make some art.

EMC: Well, we’ll have to go sometime. I’ve never been.

SLW: I can’t even articulate what it is like. One of the first things I thought about when everything hit with COVID-19 was ‘Oh my God—New Orleans! How in the world—’ That city, like many cities, but the way in which people engage in groups especially with the Second Lines and music—I can’t even imagine how it’s changed the city. But yeah, that was an incredibly rich experience. The Joan Mitchell Center is beautiful. Your accommodations, a chef that prepares meals for you, the way you sit around a giant table and have dinner together every night with the other artists, the studio spaces, and everything—it’s a dream. That I could be there for an entire three months, which is the maximum amount of time, and during the Prospect opening, was phenomenal. Joan Mitchell Center partners with the Biennial, so we had two artists who were in the Biennial who actually stayed on site at Joan Mitchell Center. We got to participate in the opening weekend gala which was just fantastic. Then, on Sunday as Prospect wound down, we had open studios, so all of these arts professionals and artists that had come into New Orleans to see Prospect from all over the world were suddenly in our studios. When you look up and see Thelma Golden from the Studio Museum, artists you admire like Ebony G. Patterson and Rina Banerjee, when you see curators from the Brooklyn Museum, MoMA PS 1 in New York as well as European arts professionals—you’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, they’re here?!’

EMC: This is serious!

SLW: You can barely—

EMC: You have to pinch yourself.

SLW: It’s really difficult to talk! So I’m fortunate I had enough wherewithal to enlist the help of a student artist. I paid her money and I said, ‘Listen, I’m going to participate in an open studio and I need someone to just sit at a table and pass out cards and manage a sign in registry.’ So although my head was spinning at the event…

EMC: You had somebody to help you. I would’ve been totally starstruck and not remembered to do anything.

SLW: Just whoa! The sheer amount of art heavyweights, curators, directors, and artists was over the top and amazing. That residency meant a lot to me and not just because of that—Prospect opened towards the end of my three-month period. What the residency provided for me was a completely new backdrop onto which I could reflect my ideas and have them sort of reflect back to me in a fresh way, in a different way. That was really fantastic.

Living in New York for the Queens Space Residency answered some long-held questions that I had. Every year I go through this process of, ‘Ok, is this the year that I should move to New York? I really should move to New York.’ When I got out of graduate school, I made a conscious choice to stay here. I wanted to be able to afford my studio and afford living. I knew that times would be hard a lot of the time, and they are. So I thought, ‘Better to be in a place you can land on a softer surface during all of that.’ So I stayed. Having a studio for a calendar year in Long Island City—was a good experience for me to have at the time. I didn’t think that having a space in New York would be a ticket to something, but this city means so much to the art global community. New York is so intrinsic to what we do as artists, as collectors, as patrons of the arts. I thought that it might overtake me somehow, that I’d be swept up in it, and I wasn’t. I was really able—and part of it was the location of the residency—but I was really able to stand back and enter that studio space as I do any other studio space. Make work and engage with the city. The whole point of New York was to get new eyes looking at the work, and I did. But it’s really difficult in New York to get people into the studio because there are lots of artists and openings and because New Yorkers are very aware of traveling distances and the logistics of travel. So just driving over a bridge or particular subway rides made planning difficult—even though the building is really conveniently located.

I had to deal with a lot of those logistics, but I still got people in and was able to make some nice, genuine connections with people that I’m happy still exist today. Those conversations are still going on today. But it’s odd, too, I thought I would spend more time going to art openings and events. That’s just something I’m not a giant fan of. I’m not an openings girl. I am and I’m not. I get into moods where I’m like, ‘Ok, yes! I want to do the opening thing.’ But generally I am not. I thought I would spend more time in museums than I did when I lived in New York. I spent some time but not as much. It was interesting. I think New York answered a lot of questions for me. I didn’t live in the city when I had that residency. I scheduled meetings and would go up every month and stay in the city a week or two and come home. Sometimes only three or four days and come back to NC. That’s the way I could make it work.

Photo: Olly Yung. © 2020 Matrons & Mistresses.

EMC: It’s interesting. That residency in some ways was such a gift. You got to try New York on for size, and realize that it wasn’t the right fit for you, without having to drop everything in North Carolina and move up.

SLW: Right. Right. I’m over that now. I don’t have that thought about making a permanent move anymore since that moment. Time in New York was also instructional for helping me to better understand my relationship to curators and museums, the importance of curators and museums and how to begin thinking about them differently. That was super important. I’ve always had good relationships with museums. I stayed here and created relationships with my museums of the region. I was fortunate in that I lived in a place and it was during the time that people were receptive. You could send someone an email and say, ‘Come to my studio,’ and they would be receptive to that. I remember when Teka Selman and Trevor Schoonmaker first came to Durham. I was a graduate student and Teka had been invited to be the guest of our Wednesday night critiques and it just so happened that my work was being discussed that night. I think there were two or three of us that would go each Wednesday, and it happened to be my turn, and that’s how I met her. The more time that I’ve stayed here, as opposed to going to New York, I realize I’ve been able to have one-to-one relationships with people that have reached well beyond here.

EMC: Absolutely.

SLW: There’s an avid group of collectors that are here in the Triangle that I’ve been able to make relationships with that have been very important. These relationships are not exclusively about purchasing my work. Many times, it results in other types of support that are also important. There is possibility everywhere if you’re willing to look around. We have great museums in the Triangle and Triad. There’s a lot here to begin with and to maintain over a period of time.

Photo: Olly Yung. © 2020 Matrons & Mistresses.

Loor, (Detail), 2015

Stacy Lynn Waddell

Photo: Olly Yung. © 2020 Matrons & Mistresses.

Loor, (Detail), 2015

Stacy Lynn Waddell

EMC: When you say that the residency made you look at museums and curators differently—it seems like you had already seen the real value in forming those relationships. How exactly did it shift how you interacted with curators and museums? Or did it just solidify, ‘Hey, this is so important and I’m really glad I’m doing it and I want to do it more’?

SLW: It solidified it. It helped me understand even more broadly the role of museums and the breadth that museums have in terms of what they’re able to do. The breadth of what they have. The Brooklyn Museum acquired a piece—to give you an idea of relationships. Everything that’s happened for me has always happened very slowly. I work slowly; I like to be able to move slowly. The opportunities that have come—people see on a CV, like, ‘Oh, this and then this and then this.’ As if you’ve orchestrated it. No. None of it. If you see something on my CV that had to be applied for, I probably applied for it several times. I can’t think of anything that I received—the Joan Mitchell Painters and Sculptors Grant, I applied for that thing—I got nominated four times. When the fourth letter came that said, ‘Oh! You’ve been nominated for it!’ I thought, ‘Psh, whatever.' I have the letter. I have a big file of letters, rejections, and otherwise and all kinds of things. I took a pen for months and just scribbled on that letter, like ‘I’m not applying for that thing.’

EMC: ‘I’m not getting attached! I’m done!’

SLW: ‘I don’t feel like dealing with this thing again!’ I wrote expletives and all kinds of crap all over that letter—still have it. And at the last minute, I think it was maybe two days before the deadline was up, I thought, ‘You know, it’s a blind nomination. You never know who’s nominating you. Someone or someones…

EMC: Four times.

SLW: Has thought enough of you and your work to put your name in the ring. You should at least apply.’ So I thought, ‘Ugh, okay.’ And I got it that time.

EMC: What an amazing story.

SLW: So, you know, it’s all been hard-won. It’s all been incredibly—it looks easy on paper, but it’s not.

EMC: Ah! You are really talented at speaking about your work! Does that come naturally to you? The couple studio visits we have had were captivating… plus you had the yummiest chocolates.

SLW: I feel so—I don’t know. It’s still very weird to talk about my work itself. It’s still very, very odd. I don’t know if I’ll ever get fully used to or comfortable with it because words feel inadequate. That’s really the main reason. Words feel incredibly inadequate to talk about something that you thought about and brought into being, and then you need to now talk about it, because that relationship we have with the work in the studio has nothing to do with words. It just doesn’t have anything to do with words.

EMC: Tell me, what does it have to do with, for you? Where does it come from?

SLW: It’s a big ball of psychic, emotional, and intellectual energy that you can’t parse out and say, this percentage is intellectual and information and this percentage is—it just sort of comes. It comes with what you’re interested in. I collect photographs—not art photographs, but vernacular images. Mostly of Black life but of everyone. I’m really fascinated in the kind of stories, the narratives behind these pictures. I am fascinated with the way in which a photograph can capture something so succinctly—and not. You can still lose it when you’re looking at it, but it can hold a kind of imprint from the artist, from the maker in a way that I quite love. So I’ve been collecting these images since the early 2000s. I have hundreds of them. They’re just snapshots. People at yard sales and tag sales and the scrap exchange, they get rid of family photos and I don’t understand why. They’re so precious. I buy tons of them and play little games.

EMC: It’s like a treasure hunt. I love going in your studio and digging in all the boxes.

SLW: Ha! There’s a lot to dig around!

EMC: There’s so much good stuff.

SLW: I lay out the photographs and I create new genealogies of people. These people don’t know each other. Photographs have nothing to do with each other biologically or in any way other than an aesthetic sense that I have or some sort of intuitive sense of, ‘Oh, these two people seem to share something.’ So I make these new sort of family trees. But most of my work, the figurative stuff, comes from photographs. A lot of the text-based pieces are my thoughts or quotes from people that I admire, like “Women are Powerful and Dangerous” from Audre Lorde, or using the title of Herman Melville’s book Moby Dick. These things that feel epic to me, these titles or phrase that have an overarching sense of power and meaning, I like to take and play around with a little bit.

EMC: One of the pieces that I wanted to make sure to speak with you about is the beautiful large piece that you have with the blue and the swans and this woman whose hand is holding up the foot of another woman… When I first saw it, I thought that it might speak to this idea that there have been other people who have walked this path before and that have lifted us up or whose paths this continued journey is built upon. I would love for you to talk about that piece, if you would.

SLW: Sure. The piece is entitled Loor. I made it for a show in 2015 for the Visual Arts Center of Richmond and the show was entitled The Epitaph of a Darling Lady. It was about the interior life of Thelma “Butterfly” McQueen. Thelma Butterfly McQueen played Prissy in Gone with the Wind, and she’s from Georgia. She was an incredibly fascinating woman.

Photo: Olly Yung. © 2020 Matrons & Mistresses.

On Left:

Untitled unique photograph, 1960

Stacy Lynn Waddell

On Right:

Untitled unique photograph, 1960

Stacy Lynn Waddell

EMC: Please—she is such a fascinating woman—I’ve loved learning about her from you. I had a whole question about her so we’re getting to…

SLW: She’s super, super interesting. She was born in 1911 in Florida and lived between New York and Georgia as an adult. You would not necessarily think that she would have had the wherewithal to demand (and expect) a kind of equity while being given this major opportunity. She did. In 1939, imagine that she made statements like, ‘In the script, there are a couple of things that I’m not comfortable doing. There are a couple of things that I don’t want Scarlett O’Hara to do to me and that I don’t want to be seen doing at all.’ Just the fact that she asked for those things, that she lobbied for herself, was empowering to me. Again, this was in 1939. She was trained as a dancer; she was young and had the opportunity of a lifetime with Gone with the Wind. But that opportunity—her most famous role typecast her. She played domestics for the balance of her career and sort of died in this biblical fashion where she was burned in a fire started from a kerosene heater. She’s been really super fascinating to me for a long time. My thought about the show was, ‘what was it like to juggle various personas, if you will, that you have to weave through and access at different times throughout your life, as a Black woman, as an actor, as someone who is never fully able to realize their full potential in their professional— albeit personal—life. What does that mean?’ There must be a great deal at work in that person, their interior life must be fascinating, because it’s probably filled with a lot of unanswered questions and deferred dreams, and what do you do with all of that? So that was what the exhibition was about, what the project was about. Loor is about the using of one’s body to go up, to advance—this idea of what it means to have your body literally be the means by which you move through all the spaces of your life. How do you elevate? How do you move horizontally or vertically? How do you transform yourself? How do you advance when it is your very body that keeps you from having the ability to do just that?

Also, when making this work, I looked back to some early works that I’d done where I’d taken Black female bodies and stacked them with sailing ships and Audubon’s specimens from his Birds of America, making a new type of totem or monument. Because anything that’s extremely vertical when you experience it as a viewer, you have to look up to see the very tip of it, and just that kind of engagement where you’re having to look up signals a kind of infinite view of something, where it could potentially be extending into that unreachable air space. This particular image is one of those. McQueen never could get to that unreachable air space. She could never get to that John Glenn-in-space, flight height, but she always endeavored, right? She endeavored to do so.

EMC: Do you consider McQueen to be a muse to you? Or do you see it in a slightly different way?

SLW: At the time I did, but I think she’s a part of a long line of independent, generous and complex Black women that I find interesting and have always admired. I’m from a family of such women, and those qualities are attractive to me—images that articulate or depict these qualities, or narratives of such persons resonate. I’m always searching for and trying to cultivate these qualities in my life as well. I think you have to have these qualities as an artist. You definitely have to as a Black woman artist. As many changes that have been made, there is still so much more to push forward. Institutions move very slowly. They’re set up for that, right? They’re set up to plan for exhibitions years in advance and decisions must go through a lengthy approval process. But I am hopeful. I’ve seen some strides being made.

A certain kind of equity can happen quickly, but that’s the quantifiable stuff. You can schedule as many shows in the next five years that feature women that do men. You can make sure that there is racial and cultural diversity. You can make sure it’s balanced; you can do the number crunching. The more difficult terrain is—how people feel about equity, how those feelings translate into financial support and how people come to understand why equity is important in the first place. This isn’t about the number crunching. It’s an inside job. It’s about the heart. This is the difficulty in confronting racism. The mass (and global) protests are not surprising at all. You can legislate, you can create laws, you can create safety nets. But, how do you change people’s hearts and their minds? Especially when these kinds of attitudes start really early, well before kids go to school. Once they get to school, the level or quality of education, who’s teaching them, how they’re deciding to design curricula, it matters. It all matters because a lack of representation just means that people are going to be written out.

At a certain level, my ongoing project is about representation; reflecting a shared humanity through my particular experiences and interests. I hope that people engage with my work, and as a result, it opens something up in them. I don’t need you to have the same relationship to the work as I do. I don’t care if you don’t read the wall text. It doesn’t matter to me. None of that matters. But I do want you to take time for slow observation and as a result, connect with something deep inside of yourself. If you’re connecting with something on the inside and especially if you’re someone who doesn’t look like me or is vastly different from me, then I’m getting there. The art is doing its job.